From the TC 372 Workshop Compendium

Do we talk about the same thing?

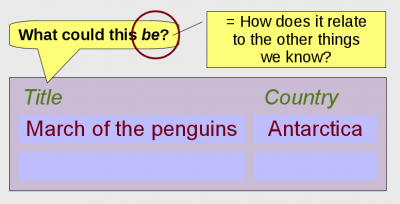

Naming a data element may appear sufficient in order to give it a meaning. While this may be true for personal databases, it clearly isn't as soon as people from different backgrounds want to share the information.

|

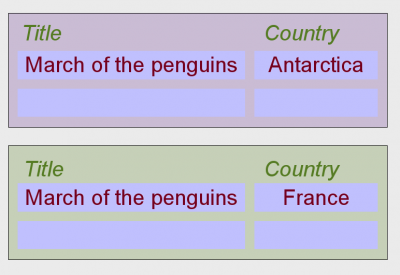

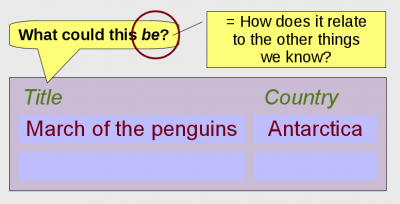

Both statements on the left appear to be correct when viewed independently from each other.

Let's assume that the first statement is from a database of documentaries for educational purposes. Most users of this database will be more interested in where the film was shot, rather than in where it was produced.

The second statement is what we would expect from a general filmographic database where films are usually associated with a production country.

|

|

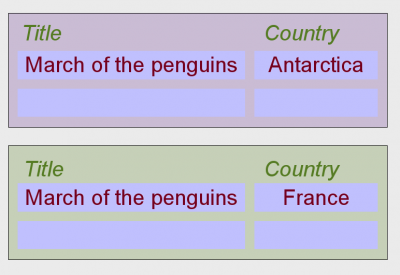

Apparently we have to consider two locations: one for shooting and one for production.

Then, "let's add another field".

In fact, having fifty or more columns (fields) in a table is not uncommon in do-it-yourself databases. Most of these columns have accumulated over time by "let's add another field"

|

|

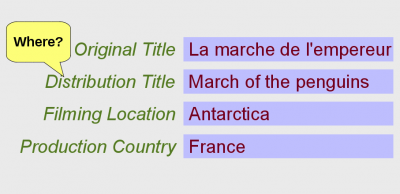

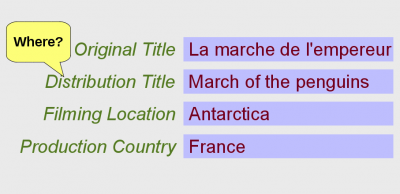

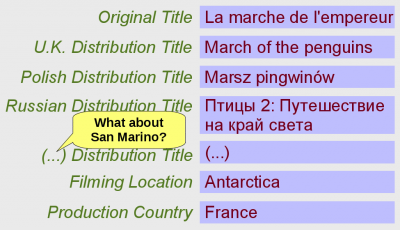

We now learn that the film was originally released in France as La marche de l'empereur. Apparently, March of the penguins is a distribution title.

Unfortunaltely, we soon come across another distribution title, Marsz pingwinów.

"Add another field?"

|

|

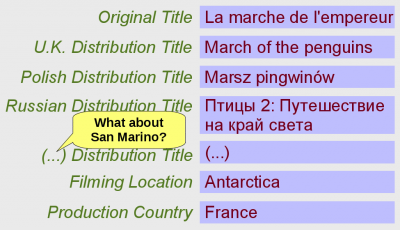

One data element per country of distribution clearly isn't workable.

After all: what does "Polish distribution title" refer to? The French original version, or a version adapted to the Polish market?

As long as we are cataloguing single copies in an archive, this question may be irrelevant. Once we start exchanging catalogue records with others, it can become an issue that needs to be resolved.

|

|

Asking what something is can easily lead us back to Adam and Eve (or to the beginning of the universe).

And, indeed, modern information science does relate things back to universal categories.

|

Clarifying the things to talk about

Metadata consists of statements about something. In this way, it is no different from ordinary discourse. Fruitful discourse requires a clear understanding of at least some basic concepts behind our words.

|

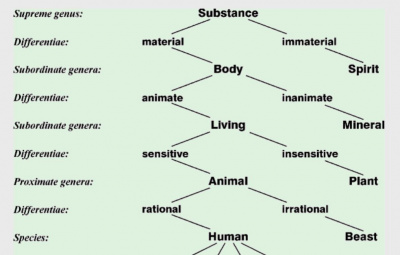

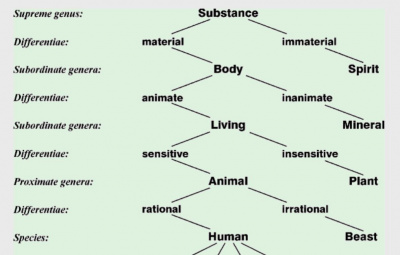

Defining classes of things by looking at how to distinguish them (finding the "differentiae") is an intellectual exercise since ancient times.

The diagram on the left shows a part of the Tree of Porphyry, derived from an introduction to Aristotelian logic written by Porphyry of Tyre in the 3rd century. This particular rendering was transcribed from a drawing attributed to Peter of Spain (1329).

|

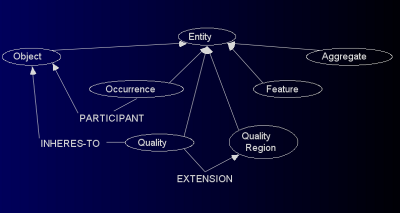

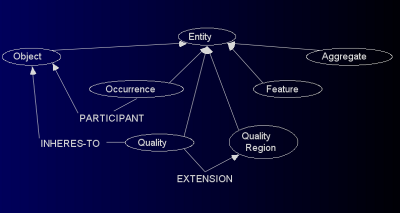

From: Aldo Gangemi: Project Proposal for a Fishery Ontology Service. Gainesville FL, 2002.

|

Here, we have a more recent example of defining top-level distinctions, including some relationships in addition to the class hierarchy.

Clarifying the philosophical perspective can be highly useful when defining models for representing domain knowledge. In this particular example, the purpose was to enuncuate some basic assumptions before developing a model for information about fishing.

|